Exposing recurring governance failures and areas of genuine progress, while also painting a clear picture of the reforms required for improvement.

Every year, National Assembly parliamentary committees publish their Budgetary Review and Recommendation Reports (BRRRs). These reports provide an unfiltered look into how the government departments and entities actually perform. The 2025 BRRR cycle exposes both recurring governance failures and areas of genuine progress, while painting a clear picture of the reforms required for improvments in governance, performance and expenditure.

From the 6th to 7th parliament - an unbroken cycle

The 6th parliament struggled to enforce accountability across government departments and entities. There were persistent issues regarding audit and service delivery failures, widespread financial mismanagement, slow or no reform, poor governance, and shielding underperforming ministers. In the 7th parliament, these same patterns continue. The BRRRs make it very clear, parliament has changed, but the government has not.

Audit failures and weak financial governance

Across departments such as Agriculture, Basic Education, Employment and Labour, Electricity and Energy, Mineral and Petroleum Resources, Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment, Correctional Services, the committees constantly call for: quarterly reporting on Auditor-General South Africa (AGSA) recommendations, early interim audits, evidence of corrective actions and consequence management. There is a strong dependence on corrective actions instead of preventative controls, which results in repeat audit findings year after year.

Irregular, fruitless, and wasteful expenditure remains a defining feature of public administration. Despite clear audit findings and action plans, many departments repeat the same financial mistakes year after year, with limited evidence that lessons are being learned.

It reveals an uncomfortable truth that the culture of accountability within government has worn out to such an extent that violating procurement rules, ignoring financial controls, or submitting unreliable reports carries little to no risk. Oversight committees flag the problems and the AGSA points out the weaknesses. However, disciplinary action rarely follows, and criminal cases almost never happen.

Vacancies, skills shortages and acting leadership

The BRRRs show that the public service has a chronic issue with vacancies in key roles, specifically CFOs, DGs, compliance heads, engineers, inspectors, ICT specialists, and critical technical staff. Many departments operate under acting leadership for years, undermining decision-making and weakening accountability.

These skill gaps are not administrative inconveniences. They are structural threats to the state’s ability to deliver. A department without the right financial, technical, or managerial expertise cannot comply with audit standards, manage complex infrastructure projects, or enforce law and policy. For example, the Employment and Labour, Electricity and Energy, and Agriculture sectors are faced with skills crises that are directly linked to a collapsing service delivery. You cannot run a country on acting appointments and empty chairs.

Underspending and budget performance failures

Budget performance shows a similar picture. Money allocated to pressing national challenges such as weak infrastructure, understaffed departments, ICT modernisation, simply goes unspent. It is not because departments do not have the resources, but because they cannot plan, procure, and implement them effectively.

Absence of consequence management

At the centre of all these failures lies the most critical issue: the absence of consequence management. South Africa’s public administration has developed a culture where wrongdoing goes unpunished. Officials implicated in failures remain in office. Investigations are stalled, and criminal cases disappear.

The 7th parliament confronts an unresolved legacy

All these threads point to the 7th parliament not confronting a new set of challenges but rather confronting the unresolved legacy of the 6th, which has worsened over time. The emerging themes of the previous parliament have spilled into the new term.

The question now is not whether Parliament can identify the problems; with the BRRRs show that it can. The question is whether it can break the cycle.

What needs to happen or change?

Although there are many recommendations made, parliament is required to shift from observing failure to interrupting it. It requires strengthened oversight tools, real enforcement mechanisms, and transparent tracking systems that prevent audit findings from disappearing into the political darkness. It needs to stabilise leadership, rebuild professional capacity, and fill appointments without any political interference. Ultimately, Parliament must ensure that the accountability ecosystem operates as intended so that resources translate into measurable improvements.

A turning point for oversight

The BRRRs do not simply diagnose a troubled state; they expose a governance pattern that has survived many administrations before it and shows no sign of correcting itself. The 7th parliament can break the cycle, or it can worsen it. The difference will depend on whether oversight – and meaningful enforcement – changes or not.

To access the 2025 BRRRs, visit PMG’s website here

Read more about our recommendations on how Parliament can improve the quality of BRRR data

Work with us

We are looking for resource and data partners!

If you or your organisation would like to contribute or collaborate, please get in touch.

You might also like

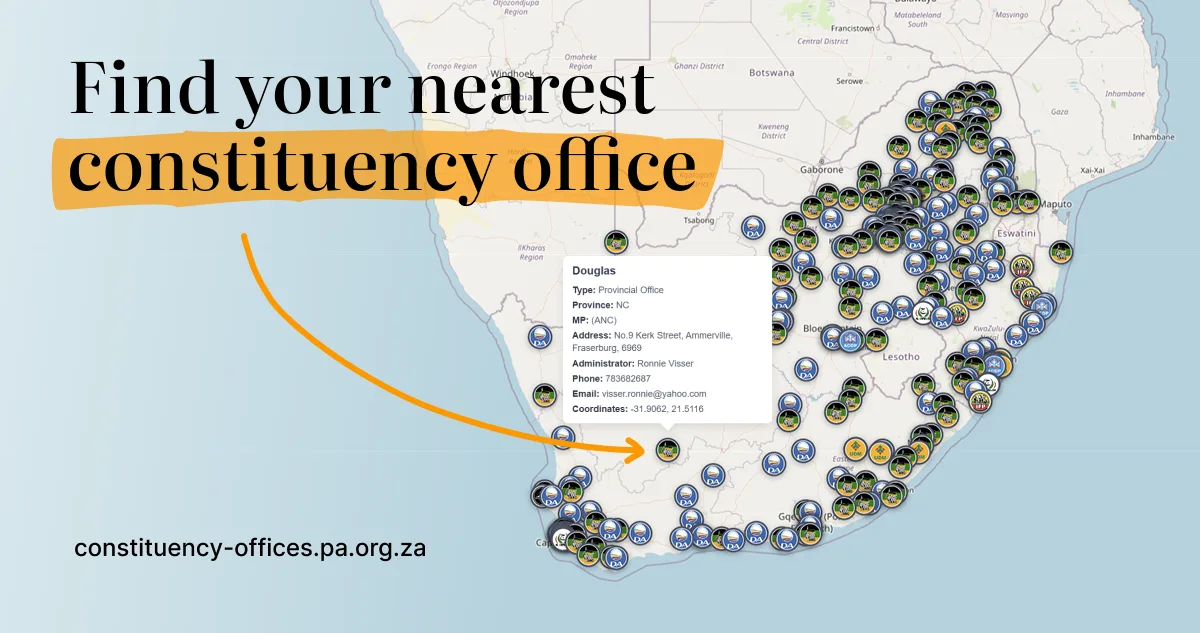

Know Your MP: Find Your Constituency Office and Make Your Voice Heard

Strengthening transparency & responsiveness: What our latest IDP assessments reveal about Parliament